Out in the cold: a critical moment for India’s wheat crop

Cold wave

In the midst of an El Niño year¹, usually associated with above normal temperatures, India has been in the grip of a cold wave during most of January. Parts of northern India saw temperatures dropping below 0ᵒC. “Delhi has also been reeling under a cold wave. Some areas have recorded temperatures as low as 7ᵒC. The cold snap has been particularly hard for Delhi's homeless people who mostly sleep on pavements.”² Extremely dense fog that has accompanied the cold temperatures affects people’s health and wellbeing, especially those with asthma or other respiratory diseases. Road, rail and air traffic has been disrupted and in several areas, schools have been closed.

Figure 1: Major wheat growing areas in South Asia, with the four dominant wheat growing states in India named (source: Mapspam)

*This figure does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of Uncharted Waters concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dashed lines represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement.

Critical moment

Impacts of cooler winter temperatures on agriculture are rarely mentioned. Yet, an analysis of recent historic climate events suggests that cold conditions could increase risk to the wheat crop that is currently growing. Wheat provides an important source of income to farmers in the Indo-Gangetic Plain, also known as South Asia’s ‘bread basket’. It is an important staple in the regional diet. Wheat can withstand low temperatures – it is grown in colder climates than India’s - but below average temperatures slow down development which in turn increases the risk of exposure to more extreme climate conditions later in the growing season.

Spring is near and inevitably the cold wave will end. A critical moment³ will be how quickly spring turns into summer. In India, climate change has already shortened the mild spring season. Summer, characterised by daytime temperatures of 30ᵒC or more, arrives now almost instantly in early March. With El Niño expected to continue for the next several months⁴, an early heat wave this year seems likely. Heat after cold has proved to be a key risk factor for Indian wheat production the past years, and one that farmers have difficulties coping with.

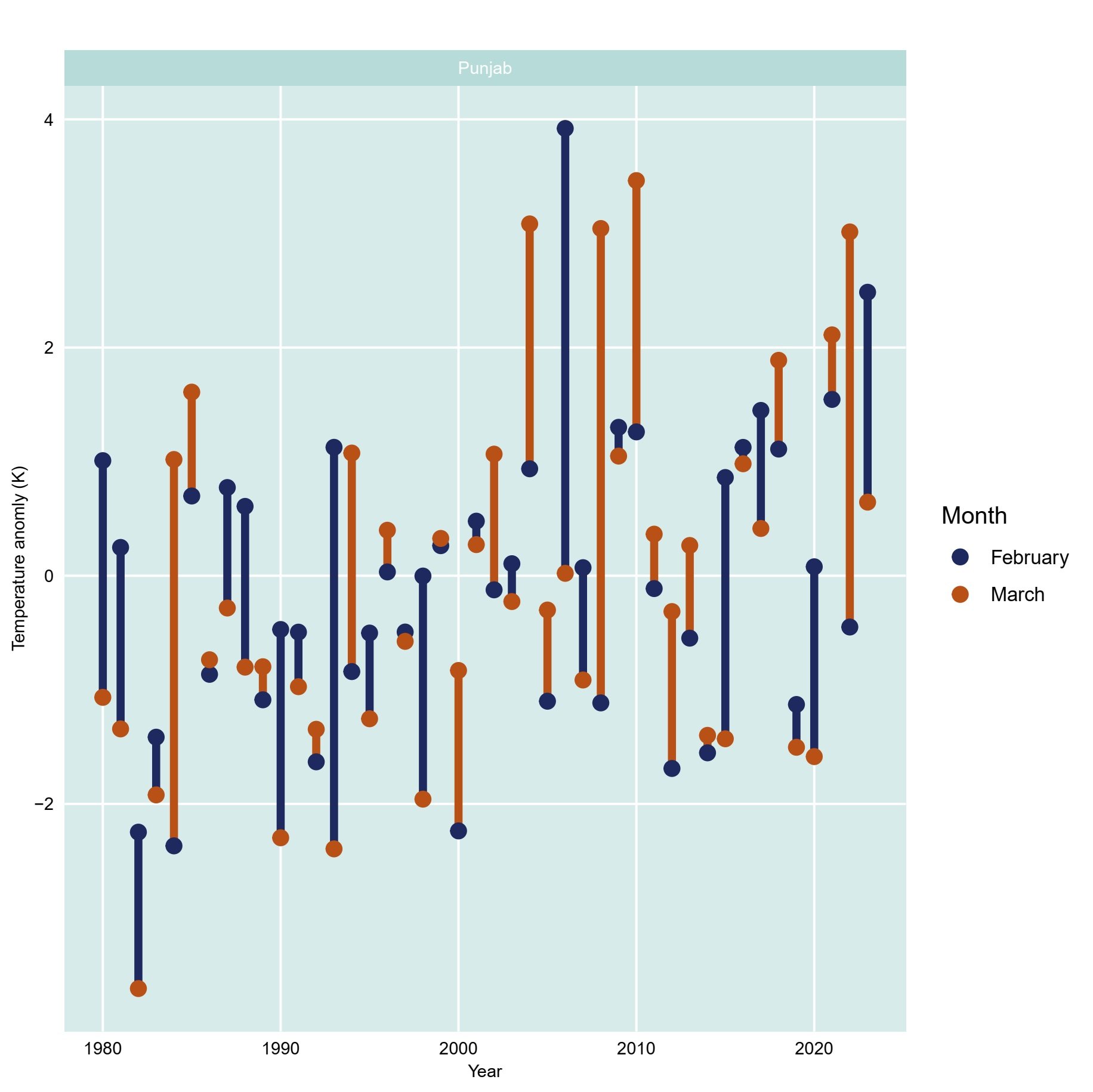

Grown during the winter months, wheat is harvested by the end of spring, before high temperatures can affect grain filling and suppress yields. Often, it is planted directly after paddy (rice), the other important staple crop. If it is planted late, or grows slower because of below average temperatures, and summer heat arrives early, serious harm can be done to the crop. An analysis of below average yield in India’s northern state shows that such yield-impacting critical temperature swings have occurred several times in the past decades, lately in 2010 and 2022 (see Figure 2). A relatively cold February followed by an above average hot March had a larger impact on yields than years with consistently hotter or colder temperatures. Another heat-related risk that increases the longer the wheat crop is left on the land is hail, which shattered yields across northern India in 2015.

Figure 2: Swings in temperature anomalies between February and March, when the wheat crop is in its grain-filling period (source: ECMWF’s ERA5). A positive(negative) anomaly means the average temperature in that month was higher(lower) than the mean temperature of the previous 30 years. The orange lines illustrate swings from below average conditions in February to above average conditions in March (blue the reverse). Rather than absolute high temperatures over the growing season, these large changes in temperature appear to impact crop yield most, especially in the traditional wheat growing states in the northwest (this shows Punjab - similar swings are observed in other northern major wheat growing states).

India, the new agri-trade pivot.

If such a swing occurs again this year, the impact will be felt beyond India. For decades, India was largely self-sufficient in its wheat and rice production, with population growth and demand matched by an equal increase in production, propelled by crop improvements and irrigation expansion, and governed by a system of state procurement, storage and price control. What happened in India, stayed in India. With yield increase and land expansion outpacing growth in national demand, India has, in recent years, become a relevant player on the global food commodity market, exporting its wheat within the region and beyond to countries like Bangladesh, the United Arab Emirates, Indonesia, South Korea and Ethiopia. Export volumes are still modest, at about a tenth of the biggest exporters and just below 3% of total global exports in 2021⁵. But its harvest in March and April falls in between those of Europe and North America in the north and Australia and Argentina to the south, which helps smooth global supply through the year.

Figure 3: Yield increase over time (in ton per hectare. source: Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, GoI & Reserve Bank of India (2022-2023 is the third advanced estimate). A clear contrast can be observed between Punjab and Haryana, India’s top growing states where yields are higher but not increasing much, and emerging states like Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, which have historically reported much lower yields but have been rapidly increasing output in recent years. In Punjab and Haryana, adverse climate conditions seem to limit further yield growth. Below average yield in 2010 and 2022 (in orange) can be explained by extreme high March temperatures following a cooler winter (a difference between Feb and March anomalies – the swing - of more than 2ᵒC and March anomalies exceeding 2ᵒC). Extreme hail damage affected the crop in 2015 across all states (in yellow). High temperatures increase both moisture in the air and convective instability, raising hailstorm likelihood and creating larger hailstones. In most regions in the world, hailstorm severity is expected to increase with climate change⁷.

Split trajectories of growth.

This increased global dependency on India’s agriculture system puts the focus on recent production increases and whether production will continue to grow at the same pace. In 2022, expectations of high exports to compensate the lack of grain coming out of Ukraine had to be revised downward quickly after the heat hit⁶. Wheat is still under export restrictions⁸. With a growing population and more affluent population, a ‘bumper harvest’ each year is merely a necessity. As other countries start to rely more on India’s exports, the world can ill afford anything less. A successful Indian harvest will ease pressure on prices globally. Sub national data reveals a split trajectory; yield growth in the major growing areas in the North west has levelled off, with below average yields in the past 15 years associated with major adverse weather events (Figure 3). Part of the historic increase here was fuelled by rapid groundwater development, especially in the northwestern states of Haryana and Punjab. Massive overexploitation has seen groundwater levels falling as a result, raising the costs of pumping both for farmers and for society with energy heavily subsidised. More towards the east of the country, farmers are catching up, increasing yields and production strongly over the past decade. While the eastern part of the Ganges has more groundwater resources and a higher rate of replenishment, it is unclear for how long current growth trajectories can be sustained. If Uttar Pradesh, the largest wheat growing state, follows the trend of its smaller neighbours, year-on-year yield increases might soon start to slow down.

What to look out for?

This agricultural year has been eventful from the start in northern India. In mid-2023, high rainfall and localised floods impacted rice transplanting causing delays and replanting. This was followed by a long break monsoon period with below average precipitation. The extent to which farmers have been able to catch up fully is as of yet still unclear. It might have merely delayed rice harvesting, or reduced yields impacting farm income and the capacity of farmers to cope with adverse conditions during the wheat harvest.

Regarding wheat, one should keep a close eye on weather conditions in late February and early March. At present there is no reason to revise wheat production estimates downward. USDA projects a yield just one million ton higher than the record year of 2021/22⁹. An early heat wave, however, can have serious consequences. Extreme hail, such as in 2015 can also be a late spoiler. India will grow a lot of wheat and diversification of production beyond the traditional main growing regions adds buffer against localized climate hazards. But despite good forecasts, lifting the export ban and large export volumes entering the market is far from guaranteed.

Uncharted Waters tracks current food production, trade and storage using our bespoke digital twin of the global water & food system. We combine process-based crop production simulations with machine learning powered trade flow modelling to analyse, in real time, the linkages between climate, water, crop production and food availability. We can deliver reliable, real-time information, fast.

Forward-looking statements are based on the Uncharted Waters’ beliefs, as well as assumptions made by, and information currently available to us. Because such statements are based on expectations as to future events and results and are not statements of fact, actual results may differ materially from those projected. All forward-looking statements reflect the beliefs and assumptions only as of the date such statements are made. We undertake no obligation to update forward-looking statements to reflect future events or circumstances.

NOAA Climate Prediction Center, El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) diagnostic discussion. Accessed 29 January 2024

Times of India. Cold wave continues in North India as mercury level dips

BBC, Delhi temperature: North India shivers under the grip of cold wave

Hindustan Times. Dense fog, cold wave grip Delhi-NCR; north India sees mercury plunge

Hindustan Times. Extreme cold in Delhi, IMD says no respite soon; dense fog grips UP, Bihar: Weather updates

Hassnain Shah et al., 2021. Climate risk to agriculture: A synthesis to define different types of critical moments. Climate Risk Management.

NOAA Climate Prediction Center, El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) diagnostic discussion. Accessed 29 January 2024

United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organisation: FAOSTAT Food Balance Sheet

USDA. India - Extreme Temperatures Scorch Indian Wheat Production. May 25 2022.

Raupach et al. 2021. The effects of climate change on hailstorms. Nature reviews: earth and environment

USDA country summary & Wheat outlook: January 2024